- In & Out AI

- Posts

- AI Music is Not Copyright Infringement

AI Music is Not Copyright Infringement

But Suno and Udio are cutting deals with record labels nonetheless.

AI is revolutionizing news & media. People are already used to getting their news summarized by ChatGPT instead of slogging through actual articles. Other forms of media - music, TikTok videos, livestreams - are next in line for disruption. Naturally, if you're in charge of a legacy media company, and some up-and-coming AI startup is nibbling away your market share bit by bit, what would you do? You'll do what you do best - sue!

The New York Times' lawsuit against OpenAI has paved the way for media companies seeking reparations from AI startups. Major record labels have followed suit by launching lawsuits against AI music startups, Suno and Udio. And nearly a year later, Bloomberg recently reported that the labels and the startups are in talks for content licensing deals.

Universal Music Group, Warner Music Group and Sony Music Entertainment are pushing to collect license fees for their work and also receive a small amount of equity in Suno and Udio, two leaders among a crop of companies that use generative AI to help make music.

By seeking to settle with the record labels, is it an admission of guilt by the AI startups that they were actually culpable of copyright infringement, as the plaintiffs claim? Absolutely not. Negotiating with the music labels to make deals is a decision to preserve the AI startups' businesses under the pressure tactics of these major corporations. Even under the most charitable lens, suing the AI music startups and seeking compensation ought to be seen as the leaders of the record labels carrying out their fiduciary duty to the shareholders by trying to maximize financial returns, and in no way can it be seen as copyright holders on moral high ground trying to take back what was stolen from them. When examined closely, the AI music startups do not pose threats to the music labels, and using songs owned by the labels for training should not be considered copyright infringement due to the fair use principles.

Why AI Music Startups Chose to Negotiate

One might reasonably ask "If these AI startups genuinely believe they aren't stealing copyrighted stuff, why would they even pick up the phone? Why not fight it out in court and prove their innocence?"

Well, because lawsuits between businesses, especially when it’s giant record labels vs. AI startups, aren't quite like a schoolyard squabble where the teacher sorts it out and everyone's friends by recess. Getting dragged into lawfare can be spectacularly ruinous for a young company, even if it is entirely in the right. It's a classic incumbent-on-challenger move: drown them in paperwork, bleed their resources, and generally make their lives miserable until they either give up, settle for pennies on the dollar, or die from exhaustion.

Startups build things. They want to ship features, iterate on their product, and find users who will give them money. Their already scarce resources - brains, time, dollars - are best spent on working on their product, not on paying lawyers to argue about the finer points of fair use for the next five years. Every dollar and every human-hour spent on depositions is one not spent on making the product better. The odds are already long for a startup; adding "protracted legal battle with a multi-billion dollar entity" to the risk register makes it even worse. Settling might mean taking a financial hit now, but it gets the legal shackles off their feet and lets the team do actual work.

The uncertainties created by lawsuits can be damaging as well. Imagine trying to recruit top AI talents: "Come work for us! We're building the future of music! Btw, there's a slight chance a court could decide our core technology is illegal in 18-24 months. We have good stock options though, so don't sweat it!" Or trying to raise your Series B: "Our user growth is explosive! Our burn rate is… also explosive, but that's largely due to legal fees! Pretty sure we can win this lawsuit though..." An early deal, even an expensive one, will clear that cloud of uncertainty. It removes the barrier to capital and talent inflows, building a healthy flywheel for the company to grow.

Moreover, inking a licensing deal with the major record labels, even if it feels a bit like paying protection money, can actually be a badge of legitimacy for the AI startups. It allows creators to use their product without having to worry about cease-and-desist letters from the copyright holders. It's still the early days of AI, and this kind of perceived legitimacy can be a key to more widespread adoption.

All these factors make a compelling case for the AI music startups to sit down at the table, even if they believe that they haven’t done anything wrong. Now, let's take a closer look at the basis of the claim "AI music is not copyright infringement."

Fair Use

The fair use principles have been the key bases for arguing against copyright infringement allegations in the US:

1. the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

2. the nature of the copyrighted work;

3. the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

4. the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Examining these principles, through both a market-driven and a technology-oriented lens, will reveal that the use of copyrighted songs by AI music startups falls under fair use.

AI Music Won't Hurt the Label Business

Let’s zoom in on that fourth factor first, as the Supreme Court has twice called it “undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use.” This factor basically asks "how much money that was originally going to the labels is now going to AI music startups".

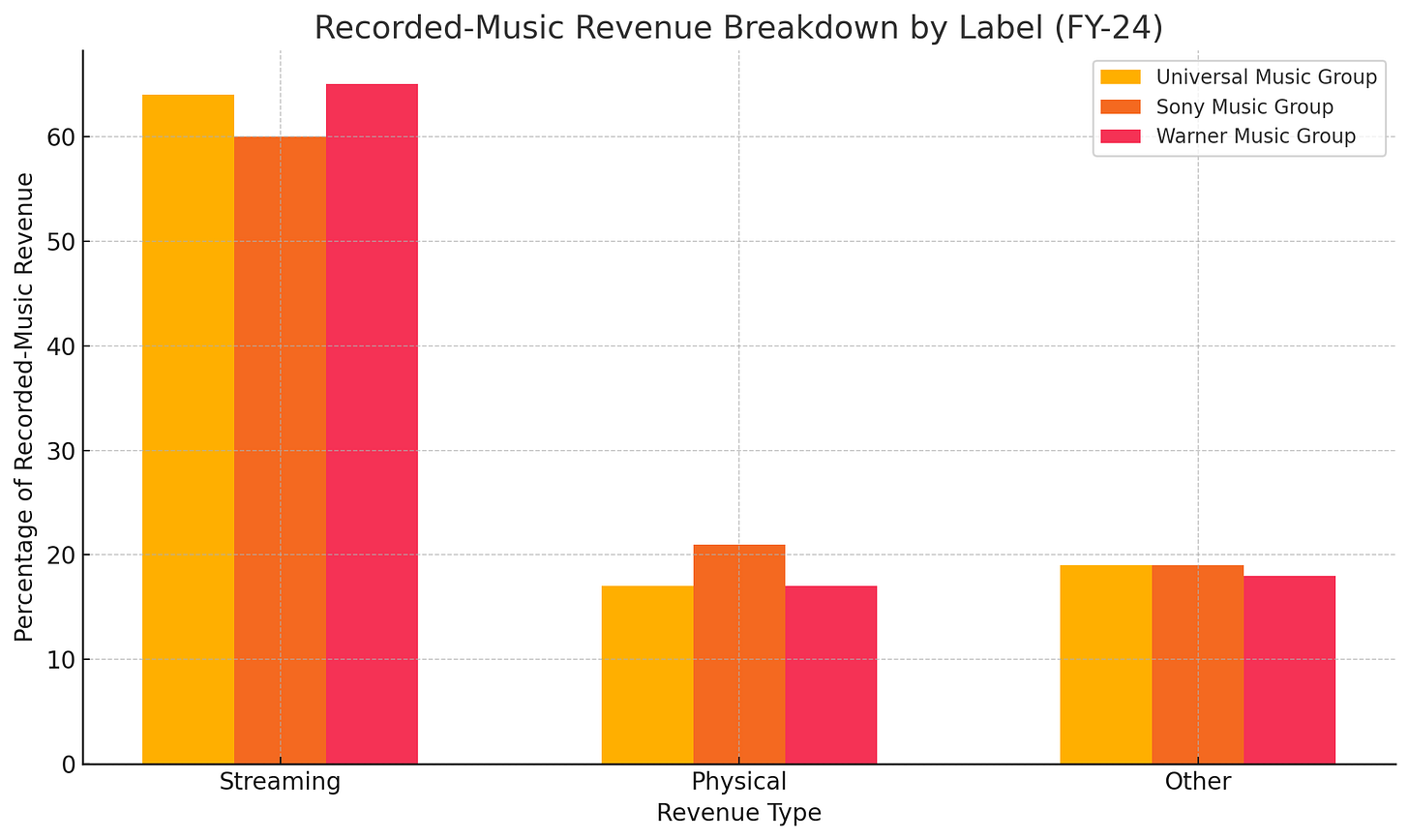

To understand AI music's impact on the labels' revenue, we'll have to understand how the labels make money. They make their money selling music (duh). Mostly from streaming, with a small portion coming from physical sales and licensing fees.

Record labels’ revenue breakdown by type.

So for AI music to really disrupt the revenue of music labels, people would need to start streaming AI-generated songs. Is that going to happen? Well, let's first look at the two possibilities for how AI music generators are going to be used:

Artists use AI music generators as a part of their creative process.

Regular folks listen to AI music directly. Either stuff made by themselves or by fellow AI-enabled amateur artists on the same app.

The likelihood of the first scenario is very high. In fact, it's basically happening already. It's just another tool in an artist's studio. Given how ‘consistent’ many of the popular songs sound these days, hardly anyone would even notice if a song is made by AI. There's no reason for the labels to be mad - Artists are going to make more songs with AI music generators, which potentially means more hits and more revenue for the labels. It's like cooks using food processors instead of chopping up everything by hand - the dishes are just as good, arguably better, and they are getting made faster and cheaper - why would restaurants complain about that?

The second scenario, where consumers ditch human artists for AI, is the one that probably keeps the leaders at music labels up at night. But that's unrealistic, to say the least. People listen to music for more than just a pleasing sequence of notes. They listen to make connections. A true fan connects with the artist – her story, what she stands for, her fashion sense (or lack thereof), and even her latest shower thoughts on Instagram. There are uniquely human traits irreplaceable by AI. No matter how perfectly an AI mimics, say, Bob Dylan's raspy voice and poetic lyrics, it's not him. And people just aren't going to listen to the AI knockoffs the same way they listen to Bob Dylan.

What about the casual listeners? Someone who doesn't follow any specific artist and just wants some background tunes for her commute? They are probably even more unlikely to listen to AI-generated music. Despite the fact that AI music generators have made making a song much easier, it still takes at least 5 minutes to generate a 3-minute song. And it's likely going to be terrible during the first few tries. More tinkering with the prompts and parameters is needed to make the song sound decent. Are the casual listeners going to have time for that? Probably not. They would much rather just pay $10.99 or whatever to Spotify and get access to a near-infinite music catalog.

The upshot is these AI music generators are far more likely to end up as another tool in a music artist's studio than a full-blown replacement for record labels. The label's sales likely won't see much damage done by AI music, and could even get a bump as more artists adopt AI in their creative process.

AI Music is Transformative

Another accusation is that AI music generators are plagiarism machines. They generate very close copies or knockoffs of existing work. However, this is not true given that the model is sophisticated enough and there is sufficient scaffolding supporting the model. If the model and the product built upon the model are well-developed, every new piece of music generated should be a completely new creative work.

When training an AI model, the training data (music owned by the labels + text content related to the music) is not stored in the models in any way, shape, or form. It is used to create a signal to adjust the parameters in the AI model (learn more about how it works here). These parameters store the patterns learned from training data, which are then used as the model's "knowledge" to combine with users' prompts to generate music.

Theoretically, a model is able to output parts of its training data verbatim. Of course the AI music startups don't want that since it would be hard to argue against in court even if your lawyer is Saul Goodman. That's why proper scaffolding is needed to prevent the model from generating exact copies of songs in the training data.

There's also a possibility that a model is overfitted. This means instead of learning the underlying principles of good music, it just learns the patterns in the training data too rigidly. So when you ask it to write a song, it would give something that sounds suspiciously similar to songs in the training data. If a model is severely overfitted, the developers are probably gonna have a hard time in front of a judge. But we’re talking about well-developed models here, so overfitted models are outside the scope for this post.

The way AI models learn to generate music is not too different from how humans learn. Both AI and humans learn by listening to a lot of songs, absorbing influences, and internalizing the patterns of good music. We don’t penalize a human for having listened to every Beatles song, as long as she doesn't make a song that sounds exactly the same as "Yesterday" and claim it as her own. The same standard should be applied to AI generated work. As long as it's not creating close copies of existing songs, it should have free rein.

OpenAI's Precedent

The other thing you’ll hear is: “What about OpenAI? They’re cutting big checks to news companies like the Associated Press and Vox Media. Isn’t that the precedent? If you use the data, you pay for the data.”

On the surface, this might seem to make sense. But there are a few key differences that make the OpenAI deals a poor justification for AI music generators to pay music labels.

First, chatbot apps like ChatGPT are much more damaging to the news companies' business than music generators to music labels. It's not a wild claim that chatbots like ChatGPT are existential threats to news publishers. Given AI chatbots’ incredible capabilities to synthesize and analyze information, they can tailor the way they present the news according to each user's specific requirements, allowing users to bypass news websites. This is incredibly harmful to website traffic and ad revenue. Thus, it makes sense for OpenAI to compensate those who actually produce the news and provide content for ChatGPT. Will AI music do the same to the labels? As we’ve discussed, probably not. It’s not really a substitute product in the same way ChatGPT is to news websites.

The second difference is how content is being presented. ChatGPT isn’t just learning from old news articles to get a general sense of the world. In some cases, it’s actively searching the real-time content on news websites and giving verbatim quotes in its outputs. This is much harder to defend as “transformative” fair use, and is clearly different from how AI music generators create outputs.

Closing Thoughts

Simply using data to train a model does not mean copyright infringement. You have to look at what’s actually going on, both with the business and the technology. And having done that for AI music generators, the argument for fair use is quite strong.

The lawsuits from the labels are nothing more than money grabs. The goal isn’t to win a landmark legal victory standing on the moral high ground. It's to make life so expensive and so uncertain for the startups that they are forced to concede and pay the record labels. In this classic startup vs. incumbent scenario, the startups have no choice but to pick the lesser of two evils and negotiate deals with the record labels. The actual legal questions regarding fair use are beside the point.

Here at In & Out AI, I write about AI headlines using plain English, with clear explanations and actionable insights for business and product leaders. Subscribe today to get future editions delivered to your inbox!

If you like this post, please consider sharing it with friends and colleagues who might also benefit - it’s the best way to support this newsletter!

Reply